I nearly drowned in second grade.

The creek in Arkansas, a stone’s throw from the house where I was born, was fairly shallow, but there was a deep spot. Of course, I couldn’t swim, but I wanted to venture out farther where Dad was playing with the other kids. I stepped into the deep hole, and although the water may have been only four feet deep at that place, it was over my head.

That is how I felt my first night in Maine for the Stonecoast MFA program. In over my head. Alone. Water above me, surrounding me, choking me.

I arrived around six in Freeport, checked in at the Inn, and looked around for a place to eat. I didn’t want the fancy restaurant at the Inn, and I remembered from the Google map I’d checked a few days earlier that there was a nearby McDonald’s. My trusty laptop showed its location was across the street.

I grabbed my coat and took off for the stairs. Near the downstairs side door, I saw a janitor and asked him about the McDonald’s. We walked to the glass door together.

“That’s McDonald’s?” I pointed at the large two-story frame house across the street. I peered closer and saw the name in small letters above the front door.

“Back when we were kids, I knew a boy who lived there,” the janitor said. “City wouldn’t allow any golden arches here, so McDonald’s bought that house.”

“Things are not what they seem,” I said.

“They rarely are,” the wise janitor said.

I thanked him for the info and ventured out into the bitter cold and crossed the street, staying on the sidewalk that was cleared of snow.

I don’t like eating alone. In the nearly deserted McDonald’s, I ate a burger and fries in four minutes, tops. Then I traipsed back to the inn and sent out a few emails, saying I’d arrived safely for my adventure, but was having second thoughts.

In the morning, I lay in bed full of self-doubt, wondering what I was doing all alone in school again. I didn’t want to get up. But I checked email and read a message from my youngest brother (a college teacher and a pilot), who said he’d fly up and get me later that day if I wanted to go home.

Breakfast alone, where the free morning buffet was laid out in the fancy restaurant, was worse than the night before because there were people and laughter and conversations that didn’t include me. I forced myself to eat slowly. Still, when you’re not talking to someone, it doesn’t take long to eat eggs and bacon. I checked my phone a couple times so I felt connected to someone, anyone.

Back in my room, I read another email from my brother. He related his own near-drowning sensation: “I remember the first day in Kentucky flying pipeline (June 8, 1989) – getting sick as we were at 200 feet and we had been at it for two hours. I was not doing the flying, and banking 60 degrees all the time causes the rider to just get ill. I was thinking I could go back to Crowder, work on the engineering degree, and go to Australia as part of the upcoming Solar Car race. No place to live, no instrument rating yet, and a lot of questions.

“Then I started doing the flying, found the duplex, met the boys – it got better quickly. And then Vic [now his wife] two years later 🙂

“The moments of ‘questioning’ are priceless and make life so much better. Aggressively learn. IT TAKES GUTS TO PUSH WHEN MOST ARE SITTING AROUND, RESTING, AND LETTING LIFE PASS. Obtaining your writing goal requires a venture into a new zone.”

At lunchtime, with a lighter step, I headed back across the street for a chicken sandwich and fries. Then school started in the afternoon, and events were scheduled day and night from that point forward for the ten days of the Maine residency that kicked off a semester’s hard work, which I’d complete at home.

I soon met other writers who I believe will be lifetime friends. The only time I ate alone was when I turned down dinner invitations and stayed in my room eating Cheez-its while I did homework before the night events started. At breakfast I sat at the same round table morning after morning, and new friends quickly joined me.

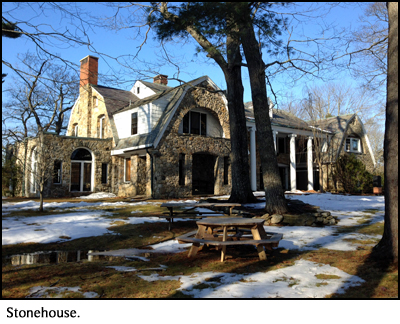

One afternoon we were later than usual returning to the Inn from Stonehouse, where our day workshops and lectures were held. As the bus arrived at the Inn, one woman complained that there wasn’t much time to eat dinner and change clothes before the night event. She wasn’t talking to me, but I said in my normal sweet voice, “There’s a McDonald’s across the street.” The woman across the aisle, her nose in the air, sneered. “Not for me.”

I felt that drowning sensation again, being pushed under, just for a teensy moment.

Next, I wondered how someone could possibly sneer at the world’s best french fries.

Finally, I thought that things are seldom what they seem, and this woman was acting uppity, but probably felt insecure. How could I know the inner workings of another writer, who was also a long way from home?

By the way, my dad saved me in that creek when I was in second grade. My brother’s words gave me courage when I felt in over my head this most recent time.

Will there be more drowning sensations in my life? I suspect so. But I’ll remember this episode of questioning where I belong, and I’ll be stronger for it.