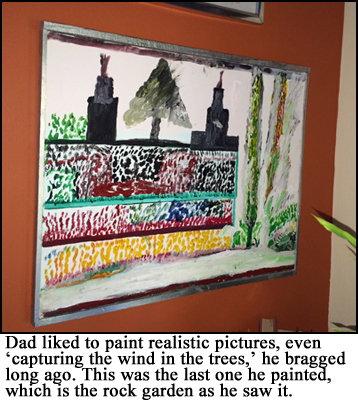

NOTE: I wrote this essay over nine years ago; my dad died a month later. I was reminded of it with all the ice water challenges for Alzheimer’s disease issued in the summer.

It’s been nearly three months since we put my dad in the Veterans’ Home. Yes, he agreed to go. We told him his medicines would be evaluated to see if anything would help his memory. He knew he had Alzheimer’s disease. We had talked about it. He said he was going crazy, and he was so frustrated trying to remember.

I wasn’t prepared for other symptoms of Alzheimer’s. He still worked around the house, raking leaves, sweeping the garage floor. But when I took him to the grocery store, he wanted to sack groceries and couldn’t. He laid the brown paper bag flat in the cart and stacked food on top instead of putting the food inside the sack. It was another sign of how far the disease had progressed.

The entire family had been helping him disguise his disease. We’d finish sentences for him. We’d recall the event he could not remember. We’d produce the names he had forgotten—even when I had to introduce him to his grandsons time and again.

When my mom would get distressed and call for relief, I’d go to Neosho and calm her down and insist that she take ‘nerve medicine.’ The antidepressants would help her deal with Dad, but it didn’t help Dad’s memory. He blew up the microwave by fooling with the wiring. He’d worked thirty years for the electric company and knew a thing or two about electrical circuits. But he’d forgotten a few things. The man who could take anything apart and put it back together was now the great fixer of the unbroken, and he was slowly destroying the house.

The call came from the Veterans’ Home that he was first on the list. But was it time? Sure, Mom deserved to be sprung from four years of house arrest, but what would it do to Dad? How I cried after that call. I knew it was a death warrant for Dad.

How long would he be there? he asked. I told him I didn’t know, but at least several weeks. The day we left him there, he said he’d be there two months. Three days later he begged me to take him home. I said no, the doctor hadn’t dismissed him. Mom and I got a nurse to distract him, and then we hurriedly left. A little over a week later, he escaped from the Alzheimer’s wing—went right out a tiny window. (I’m a little proud of that and the second time he escaped, too. Both times he was quickly found and returned.)

How long would he be there? he asked. I told him I didn’t know, but at least several weeks. The day we left him there, he said he’d be there two months. Three days later he begged me to take him home. I said no, the doctor hadn’t dismissed him. Mom and I got a nurse to distract him, and then we hurriedly left. A little over a week later, he escaped from the Alzheimer’s wing—went right out a tiny window. (I’m a little proud of that and the second time he escaped, too. Both times he was quickly found and returned.)

A trip to a hospital psych ward put my dad on anti-anxiety drugs. Then he shoved another vet, who fell. Of course, he had to be put on something that would calm him down.

Three months ago, my dad was raking leaves. Now he’s so confused, he doesn’t know where he is or who I am. His mental health has spiraled down. He is sometimes incontinent. He’s now refusing medicine and eating very little. He’s willing himself to die. On a primal level he obviously knows it is better to see what’s on the other side of this life than live in a world he no longer understands, and I agree. Jim says I lost the dad I knew a long time ago. I know that, too.

I want Dad’s forgiveness for putting him in a home, but he can no longer give it. He would forgive us anything, my sister reminds me, and he once said that we might have to put him some place. So I have almost forgiven myself for putting him where he can have constant care. I just want peace for Dad.